When I was a resident veterinarian, studying theriogenology at the University of Florida, I had a team of mentors that I would argue were unsurpassed at the time. Drs. Margo Macpherson, Malgorzata Pozor, and Mats Troedsson led our equine reproduction service; Drs. Carlos Risco and Maarten Drost taught me farm animal reproduction, and Drs. Karen Onclin, John Verstegen, and Louis Archbald guided me through canine reproduction. No other university in the country could boast such a strong, well-represented theriogenology faculty. They were all very talented, experienced clinicians, who were also insightful, meticulous scientists. A PubMed search of them as authors will yield hundreds of publications, many of them seminal papers that define the standard of care and challenge or change long-established dogma.

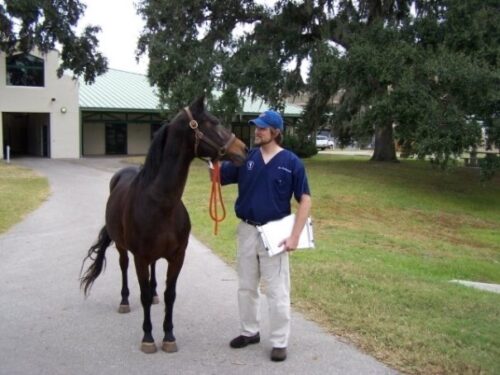

Dr. Christensen during his theriogenology residency at the University of Florida.

I was a young, inexperienced veterinarian with a stubborn personality. I know that I gave them headaches. But despite that obstacle, my mind was enough like clay that their examples and teaching molded me in both my professional and personal life. One lesson that has stuck with me is the “in my hands” argument. I remember attending a professional conference where I sat in the audience next to Dr. Troedsson during a panel discussion on equine infertility. Multiple members of the panel and commentors from the audience had shared their opinions about treatments for certain conditions that cause infertility in horses and had prefaced their comments by saying, “In my hands…” and then go on to describe what worked best “for them.” After at least a half dozen of these, Dr. Troedsson leaned over to me and whispered, “They keep saying, ‘in my hands,’ but I want them to show me the data! Where is the data?”

Exactly so. Listening to these clinicians was very confusing because sometimes their opinions were diametrically opposed. But without hard data from controlled scientific trials, all we were left with was anecdotal comments. The takeaway was that “Technique A” works for Dr. Smith but not for Dr. Jones. But why? “In my hands…” What does that mean? Were Dr. Smith’s hands just more talented than Dr. Jones’? Or was the population of horses being treated very different between the two vets? Or was the environment so different around the horses they were treating? Was the treatment in question being done in the same way by each vet? There were too many potentially differing, unknown variables for their comments to be truly useful to others trying to decide what to do in their own practices. It was a pretty useless forum.

Useless with regard to the topic of discussion. But not useless as a lesson to me. “Show me the data.” Dr. Troedsson was not just an idle, critical commentator listening to his colleagues prattle on. He had been actively investigating the problem of endometritis in mares, arguably the most important cause of subfertility in broodmares. His body of work (and that of his students and collaborators) is foundational for understanding this disease in horses and has shaped numerous treatments which are now standard for equine veterinarians. There is currently little excuse for someone to stand up at similar international forum and cite the words “in my hands” without being quickly challenged by citations of data from dozens of controlled studies supporting a defensible, reliable treatment regimen.

At the time I was a resident, the technique of laparoscopic transcervical insemination (TCI) was in its infancy. A small number of practitioners had for years been practicing a version of TCI using a tool called the Norwegian (or Scandinavian) catheter, which was manipulated blindly through the canine vagina and up to the cervix which was held in place by grasping the cervix with your hands squeezing around the abdomen of the dog and inserting the stiff instrument blindly through the cervix. It was a technique originally developed in fox-breeding farms in the Scandinavian countries. It worked well but was difficult to learn and impossible to perform in large or fat dogs.

About 25 years ago, some veterinarians began to try TCI visually using a cystoscope, which was a very stiff endoscope with moving parts. It was difficult to do, quite awkward, but showed promise. My mentors, Drs. Onclin and Verstegen, were using a different endoscope, a ureterorenoscope (designed for going into the bladder), which was thinner, a bit more flexible, and permitted injecting a little air into the vagina to allow better visualization. This technique made performing the TCI easier and its use began to take off.

I learned the TCI technique during my residency from Drs. Verstegen and Onclin. Debate at the time amongst veterinarians was fierce as to whether TCI or surgical insemination was better. The louder voices seemed to come from the proponents of surgical insemination. Surgery had for decades been the only practical option where getting the semen into the uterus was needed (e.g., frozen semen breeding). Very few vets had been trained in the Scandinavian catheter but every vet had been trained in abdominal surgery, so the popularity of surgical insemination was understandable. There was no question that surgical insemination was superior to vaginal insemination when using frozen semen. Anyone who might have offered an “in my hands” argument for vaginal insemination using frozen semen would have been dismissed by the majority. And there were scientific studies to back up that dismissal.

But TCI compared to surgical insemination was still undecided. I heard many of my colleagues say, “Sure TCI is OK, but in my hands surgical insemination is more successful.” Or, “TCI may be OK in some low-risk situations, but if you are using frozen semen from a dead stud dog, you’d better not risk using TCI. You’ve got to perform a surgical insemination.” And that seemed to be the frustrating, prevailing opinion in my early years as a theriogenologist. Meanwhile, many of us felt that “in our hands” TCI was an excellent and successful tool. My mentors certainly felt that way. And it had the benefits of being MUCH less invasive, faster, and less expensive to perform. To us, it was the obvious, ethical choice compared to anesthetizing and cutting open an animal for an elective procedure. But which technique was better at getting bitches pregnant? Where was the data?

“I have a beautiful litter of four of the cutest puppies: 2 girls and 2 boys. These dogs are the result of frozen semen TCIs and have improved their respective breeding programs by recovering invaluable genetic traits from males who were otherwise lost to the breeding pool. Thank you so much Kokopelli Veterinary Center for all of your help!”

— Tatiana Lohr, Nightguards Staffordshire Bull Terrier Kennel

“Harper with Mrs. Pam Peat and myself, awarded a 5-point major at Turlock, CA. Bred from frozen semen via TCI with Kokopelli’s expert guidance.”

— Christina Caridis, Levendi Manchester Terriers

“Bizzee Bee in Texas, showcasing her beauty in a stunning sighthound DSG. Both she and Harper were bred from frozen semen via TCI, thanks to Kokopelli Veterinary Center’s support.”

— Christina Caridis, Levendi Manchester Terriers

The data was being accumulated, but it took a few years to see some publications. Then, in 2014, a colleague from Australia, Dr. Stuart Mason, who, like me, had also been trained in TCI by Dr. Verstegen, published a peer-reviewed, retrospective study comparing data from 118 different frozen semen inseminations performed at his practice (78 TCI and 40 surgical inseminations) over the previous 2 years and showed a 45% pregnancy rate for surgical insemination and 65% pregnancy rate for TCI. This was non-biased, “show me the data” information.

These beagle puppies are the result of frozen semen breedings via TCI from deceased males—all done at Kokopelli Veterinary Center. Their breeder, Sandra Groeschel of The Whim Beagles, carefully chooses each breeding to maintain and strengthen what she is trying to create by way of healthy beagle puppies with a mixture of new and older/established genetics.

And it makes total sense. Think about it. Both TCI and surgical insemination put the semen in the exact same place: into the uterine horns. One does not get the sperm closer to the eggs than the other. The real differences between TCI and surgical insemination is that one requires putting your bitch under anesthesia, cutting her open, pulling the uterus out of the abdomen, sticking a needle through the uterine wall, and then all the ensuing inflammation that accompanies healing, and the other simply requires the bitch to stand relatively still for a few minutes while she is stimulated in a similar way as she would be if she were bred naturally. Now…which one do you think would be more likely to be more successful?

A snapshot of Dr. Christensen in the midst of a surgical insemination procedure, illustrating the invasiveness of the technique.

Dr. Christensen performing a transcervical insemination (TCI), showcasing the less invasive, more efficient approach to breeding.

I will say this, I do think that the “in my hands” camp is probably right in one respect. If you are going to perform TCI and expect good results, you do have to do it correctly. So, if you are not skilled enough to perform a TCI correctly, then in your hands surgery would be more successful. But that’s because you don’t know how to do a TCI properly. So, when someone says that “in their hands” surgical insemination works better, you can believe them. But not because surgery is better. It’s because they don’t know how to properly perform TCI.

“Pictured: Elyse & Marcel, two Long Coat Chihuahuas waiting for their turn in the Beginner Puppy Class. After many years of careful planning and research for the blending of two lines which consists of top dogs in the country, they are the result of a TCI using frozen semen at Kokopelli Veterinary Center. They have both reached their POA’s (AKC’s Puppy of Achievement), and Marcel became a 3-point major from the Bred By class before the age of 7 months old. Thanks to Dr. Christensen and his team at Kokopelli, they will make an excellent foundation to my breeding program by reintroducing important genetics from males who were otherwise no longer available.”

— Christy Smith, Petit Chenil Chihuahuas

So, maybe it seems like there’s a little bit of Kendrick Lamar/Drake action going on here and Kokopelli is laying down a diss track, but it’s not empty bravado. We have the numbers to back us up. In just the last year, we performed over 100 TCI’s using frozen/thawed semen and have a 76% pregnancy rate. That is our success rate with ALL of our frozen semen TCI’s, including all the ones with poor semen quality. If you only count the frozen semen TCI’s where we actually had over 100 million sperm (considered the minimum dose, and that is about half of our frozen semen TCI’s), we had an 86% pregnancy rate. That is approaching our rate of TCI success with fresh or chilled semen (92%). So, “in our hands,” TCI has excellent success. And we are happy to “show you the data” to back that up.

6 Comments. Leave new

I have a basset bitch that with her co owner had a TCI with frozen seman done early March 2024 the seaman was not the best quality as there were only 47 million. My birch got pregnant and two babies were delivered via c-section. The team along with Dr Christensen were great and took very good care of mom and babies. They are now 11 plus pounds and thriving. Of course we would have liked more than two but are

very happy with the outcome of this breeding. Thank you Kokopelli!!

I agree and have two litters to prove that it works.

Thank You !!!!

Thank You for sharing!

We agree and have 2 litters to add to “in our hands.” Thank you for sharing.

Данный материал будет полезен как начинающим предпринимателям, так и опытным игрокам рынка. Он поможет вам сориентироваться в быстро меняющихся условиях и выработать эффективную стратегию развития своего бизнеса с учетом международной конъюнктуры.

Цифровая трансформация в международном бизнесе: возможности и вызовы.